My Grandfather and the Moon

July 22, 2023

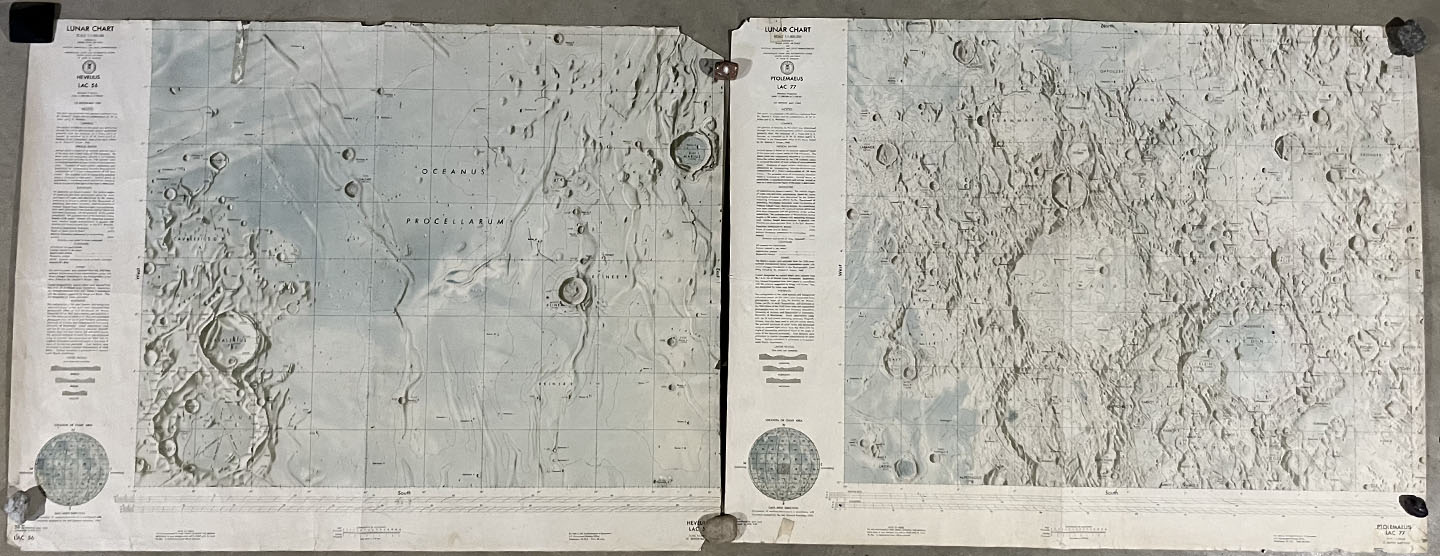

In the mid 90’s, my grandparents’ house was cleaned out after some 30 years of serving as a three story museum dedicated to a long life of science, travel, and family. Towards the end of the process, I was invited to walk through and see if there was anything I might want. My grandfather, Hollis Hedberg, was a geologist so many of the items there were naturally rather heavy (anything heavy and shiny had already been taken by more senior family members). Being only 15 or so, and not having much in the way of a long term storage situation, I couldn’t take much. I grabbed some cool looking rocks and fossils from the basement, which I still keep on my dresser. The other items I remember tucking under my arm where two poster sized maps of the moon.

They subsequently adorned several dorm room walls and other available flat surfaces for decades. They now look as though they were used by a lunar Indiana Jones - ripped corners, cigarette burns in a few spots, coffee stains, etc. I never knew exactly why there were moon maps in the basement. Family members would say something vague about like, “oh yeah - Granddad did some moon stuff a long time ago. He was on a committee once in Iowa.” Now, thanks to some new connections in my professional life, I think I understand more.

Philosopher of Stratigraphy

The first clue in establishing a more detailed history comes from the book To a Rocky Moon: A Geologist’s History of Lunar Exploration by Don E. Wilhelms, the well known USGS geologist who contributed greatly to our current understanding of lunar geology. Thanks to the gloriously done index of the book, I was able to locate the following passage with ease.

The closest the report came to the topic of the present book was in the first of many Space Science Board pitches for the inclusion of scientist-astronauts in the Apollo program, and in a contribution by stratigrapher Hollis Hedberg (1903-1988), who did no subsequent lunar work. This innovative and influential philosopher of stratigraphy recognized the great benefit-to-cost ratio of the new ACIC topographic and USGS photogeologic mapping programs.

The report mentioned in the first sentence is the 1962 publication: A Review of Space Research. This report was the result of a 3 week long Summer Study held at the State University of Iowa, in Iowa City. The session brought together scientists from many relevant disciplines to prepare a set of recommendations regarding basic research as it pertains to the mission of space exploration. The specific objectives for the summer session, as listed by the Space Science Board chair, Dr. Lloyd V. Berkner during the opening sessions where:

- “The first task is carefully to consider the future course of our nation’s scientific program in space, and to help the government’s planners to chart the way. This is a grave responsibility…”

- “The second task is similar, and involves aiding the government in its conduct of the space research program in such a way that maximum benefit will come from it.” (The paragraph goes on to request comment on how university can work with NASA, the NSF, DoD etc to train our nation’s future thinkers and doers.)

- “Let us be careful at all times to listen to each other” is the third request. I guess even then, university people and government people didn’t always know how to communicate well across their disparate stances.

The Report

The 600 page report can be found here: National Academies Catalog. In it you will find chapters on Astronomy, Celestial Mechanics, Atmosphere, Biology, etc. Some interesting sub headings include: Preliminary Report on the Use of Lunar Satellites for Fundamental Experiments on Gravitation, Interaction of Solar Radiation with the Earth’s Atmosphere, Magnetic Fields in Space, Impact of the Space Program on the Economy, and more. However, chapter 4 on Lunar and Planetary Research contains a section, B-2, called Lunar Topographic and Photogeologic Mapping, reproduced here:

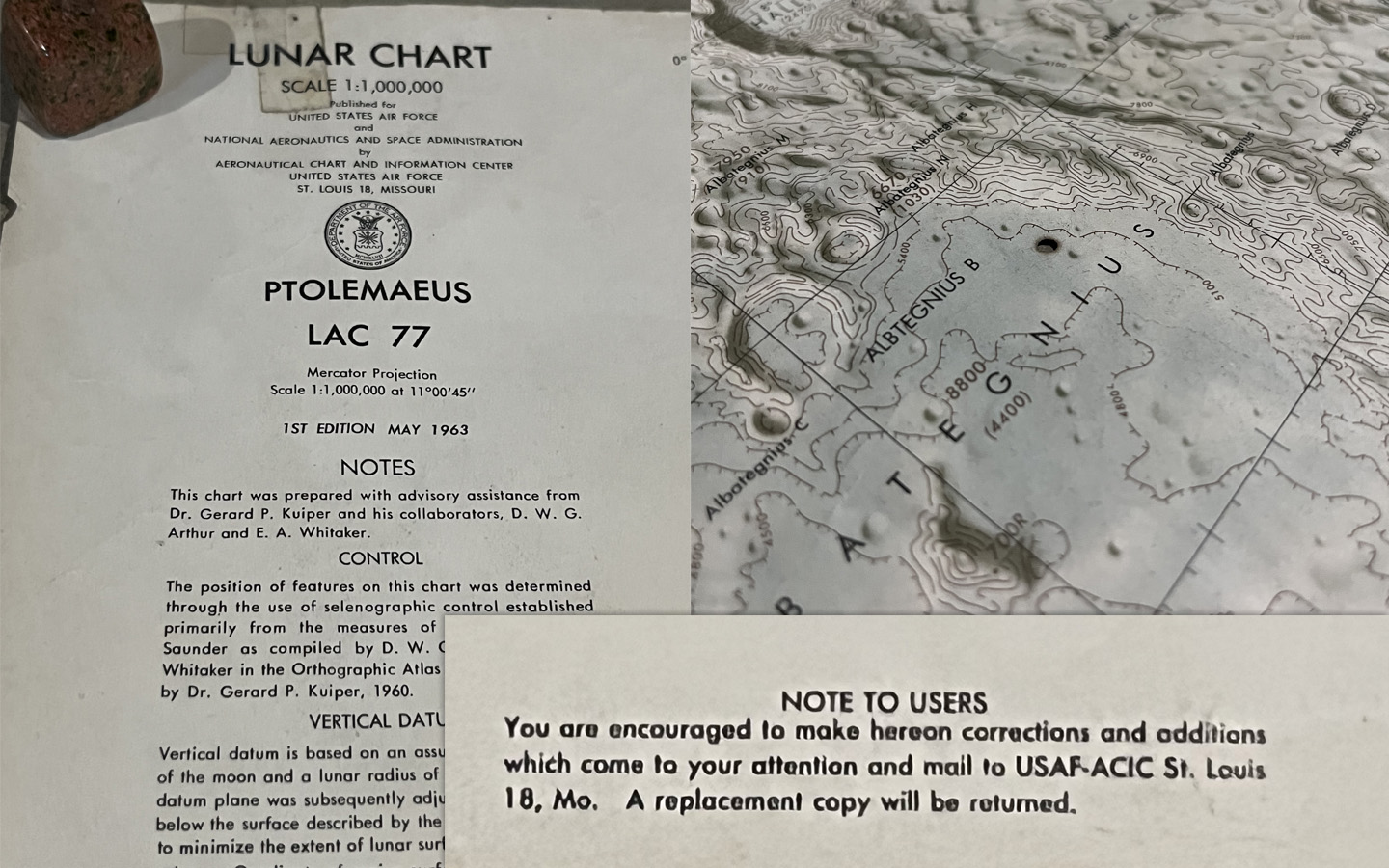

B.2 Lunar Topographic and Photogeologic Mapping

Hollis Hedberg

It has been recommended that mapping of the topography, geology, and other features of the Moon's surface be accelerated, and that increased emphasis be placed on the early completion of the Air Force LAC series of lunar maps and on the U.S. Geological Survey' s photo geologic analysis. Photographic interpretation has already provided the major part of our available information on the geology and probable history of the Moon. The presently programmed Air Force Series of eighty-four 1:1,000,000 topographic maps of the visible portion of the Moon, of which only six are yet available, should be pushed to completion. The geological interpretation of one of these quadrangles by the U.S. Geological Survey (Shoemaker) demonstrates the large amount of information which can be obtained by modern photogeologic methods and the need for expediting photogeologic analysis of other selected quadrangles. The U.S. Geological Survey technique of combining photogeology of the Moon with detailed study of potentially analogous features on the Earth is one of the major sources of new ideas on possible lunar conditions, history, processes, and scientific techniques.

It has been stated that urgent objectives are general topographic and geologic maps of the entire lunar surface (both sides of the Moon) and detailed maps of certain areas of most critical significance. Among the most important contributions to the attainment of these objectives will be comprehensive high-quality television photographic coverage, with stereoscopic overlap, of the entire surface (both sides of the Moon) through lunar orbiters, and detailed television photography of local areas through landers. The program should place particular emphasis on providing adequate support for the large amount of interpretative study and map-making necessary to get the most information from both presently available photographs and those which may be obtained in the future, on assuring adequate Earth-based telescope facilities for those engaged in this work, and on assuring opportunities for comparative study of similar Earth and ·Moon features. In terms of useful information received per dollar spent, these topographic and geologic mapping studies have been and probably will continue to be among the highest yield investments of the space program.

The gist: Make more maps of the moon! It’s cheap and will be very useful.

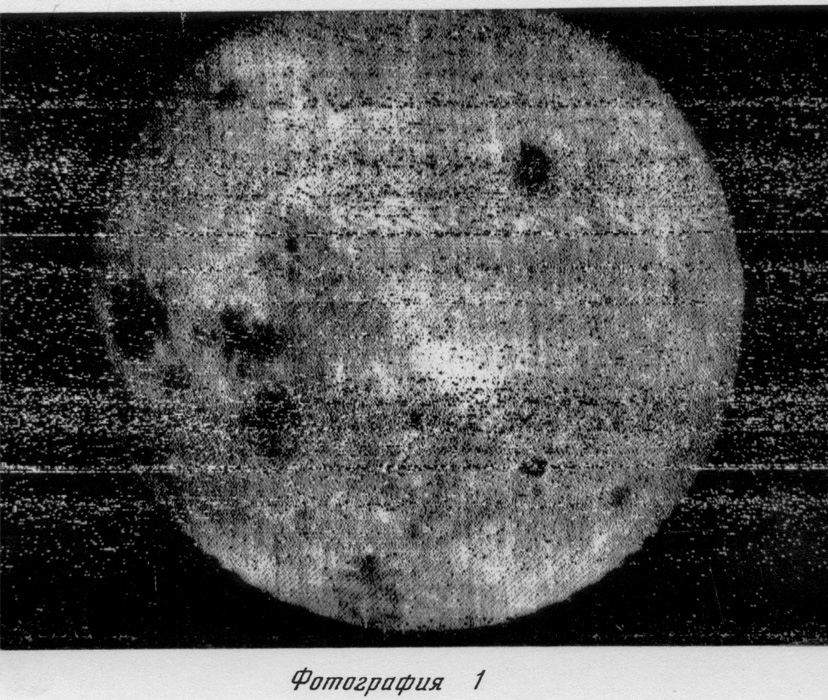

For some historical context, the first images of the far side of the moon where less than 3 years old when the Summer Study convened. The crude images were taken by the soviet craft Luna 3. John Glenn had become the first American to orbit Earth in months before the meeting in February 1962. Kennedy’s We choose to go the Moon speech would be delivered a few months later in September. Having myself grown up during the era of routine shuttle missions, it’s hard to imagine how unknown the moon must have been even to scientists in the summer of 1962.

Exactly how the report was received by the ‘government people’, and what actions were taken as a result, is of course beyond the resolution of my history lenses. Yet, the moon was mapped! The series of Lunar Charts mentioned in the quote above reached a total of about 40, covering the central region of the near side (catalog is here: Lunar Chart Series). They were created using telescope images from observatories on Earth. However, soon the lunar orbiter missions would return many more images of the moon while in orbit (i.e. much closer), ushering in an era of new mapping techniques.

References and more:

-

Biography of Hollis Dow Hedberg from the National Academies: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/2037/chapter/12#215

-

To a Rocky Moon, Don E. Wilhelms https://www.lpi.usra.edu/publications/books/rockyMoon/

-

A Review of Space Research https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/12421/a-review-of-space-research

-

Lunar Chart Series https://www.lpi.usra.edu/resources/mapcatalog/LAC/

-

Lunar Cartographic Dossier https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19760010934

-

Luna 3 image collection https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/imgcat/html/mission_page/EM_Luna_3_page1.html

Share on: